Treating a hidden livestock and poultry profit robber in new ways

Leaky Gut Syndrome (LGS) has many triggers, making treatment a challenge. Dedicated research is nearing a solution for this costly livestock and poultry issue.

May 1, 2018

Sponsored Content

You’ve got a heifer calf, feeder pig or broiler that, no matter how much it eats, is just not putting on weight like it should. The animal is not showing a single outward symptom of illness, leaving you at a loss in diagnosing the issue and treating its source.

Maybe it just doesn’t have the growth potential of its peers. Maybe it’s genetics. Or, it could be an issue that, left unchecked, can erode efficiency and, ultimately, profit potential for producers.

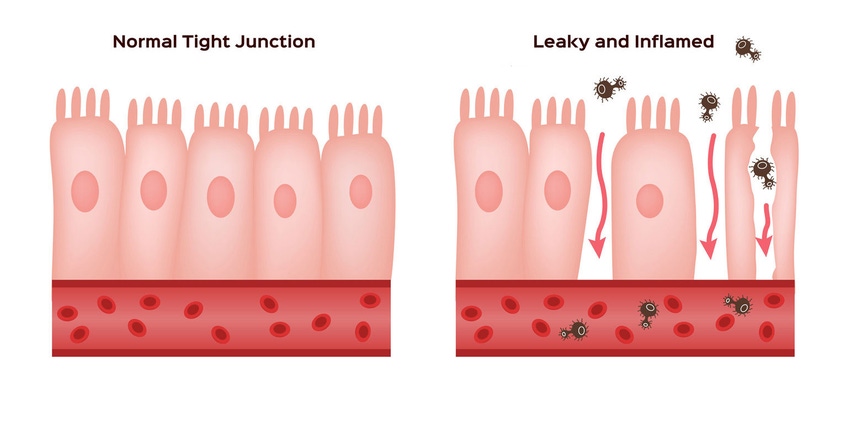

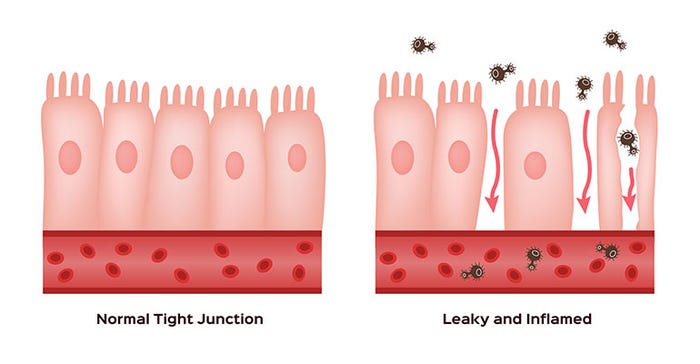

Leaky Gut Syndrome (LGS) is a subclinical infection affecting just about every ruminant and monogastric animal in the livestock and poultry sectors. The infection targets the structure of the small intestine, causing discomfort and leading to slow or weak weight gain. It creates conditions under which critical digestive system structures are damaged, intestinal walls become permeable and nutrient digestive absorption declines. It causes some animals to eat less, while in others, it simply causes more of the feed that’s consumed to escape through the digestive system before nutrients can be absorbed and the animal can gain weight.

Once an animal has the condition, LGS doesn’t necessarily exhibit symptoms on a consistent basis – a major complicating factor for diagnosis and treatment. If happening with a high frequency, it does worsen with each subsequent case as intestinal tissues incur more damage. But those tissues do eventually recover if given enough time, usually in under two weeks. Some infected animals can live their entire lives without LGS becoming symptomatic.

Antibiotics have historically been the most common treatment for leaky gut. But, antibiotic resistance and falling consumer acceptance are leading the industry to seek other alternatives.

Leaky Gut Causes

There’s no single source of LGS. Environmental stress, harmful bacteria and the consumption of mycotoxins are common causes of LGS in livestock and poultry, however. In general, animals become symptomatic when toxins that ordinarily are absorbed and excreted through the intestinal tract instead inflict damage on digestive structures like villi and permeate through intestinal walls. The toxins then enter other parts of the body and spread infection.

In some cases, damage comes through the reaction of an infected animal’s body. Under normal conditions, a certain percentage of the energy an animal derives from feed is devoted to digestion. If LGS is present and opens the door for other infections, a larger share of energy may ultimately be directed at staving off those infections. This is a common source of economic losses from LGS, especially in cases when it does not become symptomatic.

“The system is constantly challenged and under repair, and the animal has to devote a significant amount of energy to that process. About 20 percent of total protein consumed goes to intestinal function under normal circumstances, whereas if it has to work harder, that rate is going to be higher,” according to Venkatesh Mani, Associate Scientist at Kemin Agrifoods North America. “Protein that’s supposed to be used for growth and to put on more muscle is instead used to repair intestinal tissues.”

Leaky Gut Syndrome is common across different species, and its danger is two-fold, Mani says. Beyond the gradual decline in expected weight gain, infected animals are left more susceptible to other infections, both conditions that can lead to economic losses for producers.

“Growth will be retarded in an animal infected with leaky gut compared to a normal animal, and it might be made more prone to contracting other diseases. If a disease like porcine epidemic diarrhea virus or E.coli is present, it is going to continue to thrive. There is also the possibility that hormones like cortisol will be excreted,” Mani says. “In general terms, if it is a milder case, you probably are not going to notice it and animals aren’t going to show any symptoms. In other cases, it is a gradual problem. If a finished hog weighs 280 instead of 300 pounds, it will be more difficult to notice. The animal may weigh less, but it may be difficult to pinpoint the source of that loss.”

Environmental, Feed Triggers for Leaky Gut

Environmental stressors – namely heat – are common triggers of leaky gut syndrome. Challenging conditions can lead the animal’s body to excrete hormones like cortisol that can inflict damage when absorbed into gut tissues or require more of the animal’s energy to combat, taking that energy away from weight gain.

Like other toxins, these hormones can inflict even more damage if that absorption and resulting leaky gut occur with greater frequency. Gut tissues recover relatively quickly, but repeated bouts with LGS can cause a gradual erosion of those tissues when too little time passes between flare-ups caused by the environment.

“Environmental factors like heat and crowding are inherently frequent,” Mani says. “Heat stress is a big issue and very important to how much leaky gut affects the animal. When there is any sort of stress like this, digestion breaks down and when intestinal barrier disruption happens, it can lead to leaky gut via the breakage of the junctions between epithelial cells creating the intestinal walls.”

The absorption of toxins in feed can lead to similar tissue destruction. Aflatoxin in corn is a common mycotoxin that can promote LGS, even at levels well below the 20-parts-per-billion (PPB) threshold for acceptance into the feed supply. As little as five PPB can cause even a mild case of leaky gut to become symptomatic and lead to a decline in weight gain, Mani says.

Managing Leaky Gut and Maintaining Gut Health

Historically, conditions like leaky gut have been handled with antibiotics. More recently, supplements like probiotics and antioxidants have been shown to help manage LGS, an increasingly attractive set of options as some sectors of the livestock industry face pressure to cut back antibiotic use or become antibiotic-free altogether. Because of the variability in LGS causes and triggers, however, it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact remedy that will be effective.

“We know that mycotoxins can cause disruptions in the gut, so by removing them from the feed, we can remove one cause,” Mani says. “But, leaky gut happens for a variety of reasons.”

There are other products that have promise in managing leaky gut, not by targeting the specific causes or triggers, but instead by focusing on the basic structures they affect. Butyric acid, for example, can serve as a basic energy source for epithelial cells and tissues, like those that make up the small intestine. Higher levels of the short chain fatty acid have been shown to strengthen those epithelial tissues and the binding proteins between them, and increase antioxidant levels, which helps minimize hypoxic conditions that are favorable for leaky gut’s development.

A new platform of products from Kemin offers an answer to preserving producer profitability while ensuring the animals meet evolving consumer demands.

Tackling Leaky Gut Treatment

Encapsulated butyric acid feed additives from Kemin, ButiPEARLTM and ButiPEARLTM Z – which contains both butyric acid and zinc – combat the specific conditions that otherwise would be favorable to LGS. Kemin research has tested the positive gut health effects of supplementing diets with both encapsulated products, with consistent results.

“It was hypothesized that combining butyric acid and zinc would have beneficial effects toward the intestine, particularly if supplemented during a stress condition, like inflammatory challenge or heat stress,” according to a Kemin research report. “The data presented provides evidence ButiPEARL Z (butyric acid and zinc) helps to protect the cells from inflammatory challenge as well as heat stress. Under inflammatory challenge and heat stress conditions, ButiPEARL Z treated cells performed better than other treatment groups. This indicates that beneficial effects of butyric acid and zinc can be obtained through a combination product like ButiPEARL Z.”

In research specific to poultry, the extended value of these findings starts to clarify. Supplementing with butyric acid and zinc decrease the triggers for leaky gut and has other positive health outcomes.

“Adding an encapsulated source of butyric acid and zinc to the broiler diets provided an improvement in feed conversion at each feeding level throughout the duration of the trial,” according to another Kemin research report. “Foot pad scores showed a statistical reduction of scores. This suggests drier excreta on the floors may lead to fewer lesions on the feet of birds.”

The research results show that a product like ButiPEARL Z has the potential to both minimize the negative effects of these common stressors on overall gut health, and take on the specific physiological effects that promote damage from leaky gut.

“If you are supplementing animals with ButiPEARL Z before they are exposed to heat stress, those animals may experience less stress. There is less damage than animals not supplemented,” Mani says, adding that more research can expose how such additives can help manage similar triggers for the condition.

With the promising results the ButiPEARL products have shown thus far and research that continues to connect specific potential compounds with both the causes and effects of LGS, Mani says the use of antibiotics could be greatly reduced in an industry that’s facing mounting pressure to do away with them. Further research is on the horizon to explore additional benefits of alternative products.

Check out the Kemin Gut Health Solutions product lineup and get your personalized solutions at Kemin.com/GutHealth.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like