Knowing where anthrax exists helps national authorities and livestock producers plan vaccination strategies.

May 13, 2019

Newly published maps reveal, for the first time, where anthrax poses global risks to people, livestock and wildlife, according to the University of Florida.

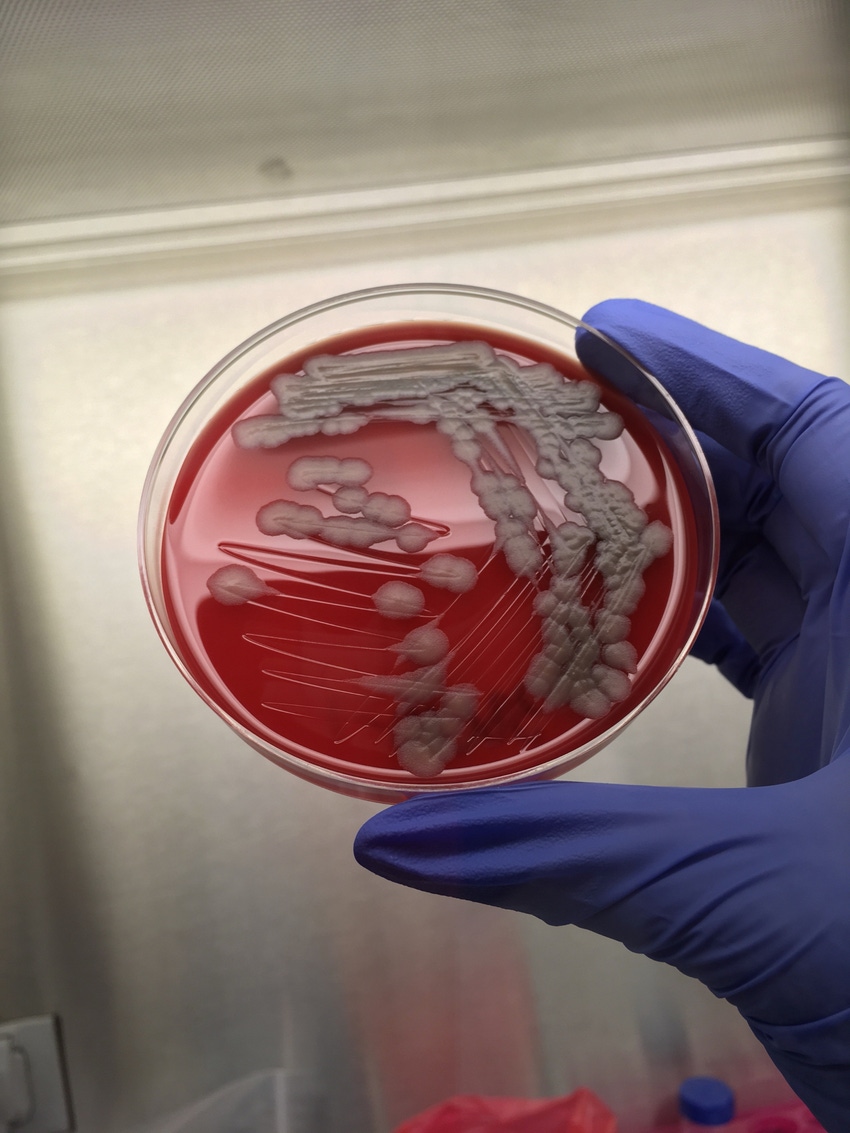

Popularly viewed as a frightening airborne agent of bioterrorism, the bacteria that causes anthrax infections — Bacillus anthracis — naturally occurs in the soil on every continent and some islands.

The maps, published May 13 in Nature Microbiology, are the result of 15 years of data collection covering 70 countries compiled by Emerging Pathogens Institute associate research professor Jason Blackburn and his colleagues. Until now, the geographic distribution of anthrax had not been mapped globally.

“Our main purpose was to describe where anthrax occurs, or is likely to occur, across the globe and to illustrate sub-national areas where surveillance is necessary,” Blackburn said. “Anthrax is a disease that affects both animals and humans, and it is most commonly associated with rural and agricultural communities, which contend with it nearly worldwide. Our maps will help countries and health authorities focus on specific anthrax-prone areas to target control and surveillance.”

Blackburn, who is also an associate professor in the University of Florida’s geography department, and his team mapped known occurrences and suitable habitat of B. anthracis as a proxy for disease risk. They then overlaid this with models showing where people, livestock and susceptible wildlife occur.

Co-first authors Colin Carlson, an environment initiative postdoctoral researcher at Georgetown University, and Ian Kracalik, a Centers for Disease Control & Prevention epidemic intelligence service officer (and former doctoral student of Blackburn’s) led the modeling portion of the project.

The team found that 1.83 billion people inhabit anthrax risk areas, but they trimmed this down to 63.8 million workers who engage in agricultural occupations that place them at heightened risk of contracting the disease, the announcement said.

Likewise, they mapped livestock by species type and found that anthrax-vulnerable areas contain 1.1 billion livestock.

“This tells medical clinicians and veterinarians that if they are inside a predicted zone, anthrax should be on their routine diagnostic list or their annual vaccination list, respectively,” Blackburn said. “The best way to protect people is to routinely vaccinate livestock.”

Although an effective livestock vaccine exists, it must be given yearly, and the maps will help authorities prioritize using it where the livestock/people interface is greatest. The pathogen can persist in a nearly indestructible spore form in soils for several years to decades, which means that sustained vaccination campaigns are necessary in some regions, even when there are no known outbreaks.

“There's some incredible patterns in our results, such as how the legacy of Soviet vaccination campaigns persists to today, but there's also some very visible impacts of poverty in places where anthrax is hyper-endemic, and I hope our work draws more focus towards that,” Carlson said.

Areas of sub-Saharan Africa and South and East Asia tend to have vaccination rates ranging from 1% to 6% — but the researchers found that these regions disproportionately account for 48.5 million rural poor livestock keepers.

“Internationally, we need to do a better job of getting the vaccine to high-risk areas,” Blackburn said.

Between 20,000 and 100,000 people report contracting anthrax annually around the world, and most occurrences are in poor or rural areas. It is rare for someone in the U.S. to contract it due, in part, to high rates of livestock vaccination in disease-prone areas. These numbers are incomplete, because many subclinical cases go unreported for various reasons, including stigma, fear of quarantine or lost income or lack of an accurate diagnosis, the researchers said.

Reported figures are even weaker worldwide for livestock and wildlife, they noted.

The research has implications for wildlife of conservation priority, such as wood bison and saiga antelope, as well as economically important game animals such as white-tailed deer. It is not feasible to vaccinate wildlife, Blackburn noted, “but knowing where anthrax is likely to occur can inform hunters as well as livestock growers, who have close proximity to this wildlife, to prevent spillover events in either direction.”

Outbreaks occur when hoofed mammals consume the soil-dwelling B. anthracis, which sticks to grasses or browse. In the U.S., wildlife and livestock outbreaks tend to occur between May and October.

People most commonly acquire B. anthracis through skin lesions when they handle or butcher infected carcasses. Eating infected meat can also cause illness and lead to deadlier outcomes, the researchers said. How sick someone becomes is determined by how they were exposed.

Blackburn’s future work will examine the genetic diversity of B. anthracis worldwide and the geographic factors associated with specific genetic strains.

“This species can be found in many different environmental conditions,” Blackburn said. “Knowing how the strains are distributed, and how effective the vaccine is against different strains, will help us to further refine our risk maps.”

Source: University of Florida, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)