Can the beef industry meet the challenge of building on such pilot programs and achieving the type of traceability our export markets increasingly demand?

June 16, 2021

By Robert Hemphill

Will beef produced in the US ever be traceable? Some beef already is. Companies exporting under the USDA’s Export Verification Program must meet a number of requirements, including information on the origin of the beef. Walmart is now selling beef under its own label, McClaren Farms, where cattle are tracked from birth to processing. The McClaren Farms label represents the maximum traceability one can expect in beef sales (not including locally sold beef), and the company cites consumer demand for traceability as a prime motivator. Consumers receive benefits from improved traceability systems by consuming safer food and gaining knowledge about how their food is produced.

The vast majority of US beef, however, is not traceable, despite the many benefits of traceability and the fact that most major beef exporting countries have more advanced traceability systems than the US. The major reason for our lack of progress seems to be rancher opposition to a government-led traceability system. So if the US is going to remain competitive in beef export markets it must achieve traceability on a voluntary basis.

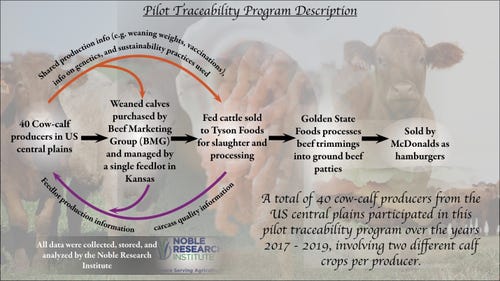

The paramount question then becomes: what sort of voluntary traceability program would be viewed favorably by US ranchers, especially those at the cow-calf level? Recently a consortium of the beef supply—from 40 cow-calf producers to a fast-food restaurant—sought to identify such a program and test it at a pilot-scale. For my master’s thesis I interviewed 15 of the 40 cow-calf producers and concluded this pilot program can indeed serve as a prototype for a successful voluntary program at a larger level.

The pilot program involved cow-calf producers selling preconditioned calves to a marketing group, where the cattle were raised in the same feedlot. The cattle were then processed by Tyson Foods, with the beef trimmings used by a single wholesaler to make ground beef patties for subsequent sale at McDonalds. From birth to slaughter the cattle were fully traceable.

This program was designed to specifically appeal to cow-calf producers because it actively involved them in the design of the program and sought to exchange useful information upstream and downstream the supply chain. Ranchers provided the feedlot and processor information on cattle genetics, vaccinations, and other health treatments. In turn, the rancher was provided information on feedlot and carcass performance. All data sharing was handled by the Noble Research Institute, a non-profit research organization, who ensured the data were shared at a level of confidentiality that appealed to the ranchers.

For example, when a rancher received feedback on feedlot performance, their cattle were compared to the performance of all other 39 ranchers at an aggregate level, so that no one rancher knew how any one other rancher’s cattle performed. This provided ranchers the information they needed to improve their operation while also ensuring confidentiality. Moreover, because ranchers trusted the Noble Research Institute they felt confident that the processor and others downstream the supply chain only received information that ranchers agreed to release.

After the program was complete I interviewed fifteen of the 40 ranchers, asking questions about things they liked and did not like about the pilot program and, if it continued, whether they would continue participating. A large majority indeed wished to continue participating in the program, and most criticisms of the program were largely cosmetic (often caused by miscommunication) and thus easily remedied.

The interviews made clear the reasons for the project’s success. First was the important role that the Noble Research Institute played, suggesting that widespread traceability requires the involvement of organizations trusted by ranchers. Second is involving ranchers in the design of the program, such as the identification of which information will and will not be shared. Third is the program’s focus on delivering benefits to ranchers in terms of feedlot and carcass performance. As this was an actual pilot program and not a hypothetical exercise, its success suggests that the program can serve as a foundation for building a large-scale traceability system that will be viewed favorably by many cow-calf producers.

In addition to evaluating the pilot program the interviews asked about a number of other traceability issues, and the responses are useful in speculating on how the pilot program can be scaled. First, it is unclear the extent to which the USDA is seen as a trusted institution by ranchers, so one should not just assume the USDA can fulfill the role played by the Noble Research Institute. Second, ranchers seemed to best understand the need for industry-wide traceability in terms of animal disease management, so programs that focus on prevention and containment of diseases like foot and mouth disease will be viewed more favorably than those that stress consumer demand for traceability. Third, ranchers hold a contradictory view of responsibility that a traceability system will need to address. When it comes to disease outbreaks ranchers do not want to be held accountable for the actions of other ranchers, but at the same time want amnesty for any problems their cattle pose for supply chains. This contradiction is resolved somewhat when you realize they are mostly fearful of being falsely blamed by downstream supply chain actors for problems those actors actually caused. This reflects the long-held and perhaps irresolvable distrust some ranchers have of their buyers.

Can the beef industry meet the challenge of building on such pilot programs and achieving the type of traceability our export markets increasingly demand? There is reason for optimism. The industry has a history of establishing non-profit organizations that facilitate cooperation. Certified Angus Beef is a prime example (pun intended). Ranchers do indeed see the need for traceability, at least in animal disease management. The real question is whether ranchers will step up to the plate and play an active role in how traceability programs are designed, and not let their natural distrust of the downstream supply chain obscure the benefits that cooperation can provide.

Robert Hemphill is a former graduate assistant in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Oklahoma State University. The full thesis from which this article was derived is available at http://dasnr39.dasnr.okstate.edu/hemphillthesis.pdf.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)