N&H TOPLINE: Taking on sheep parasites with spider venom

Besides searching for anti-parasitical compounds, researchers turn to arachnid venom for new compounds to treat antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and cancer.

Internal parasites are getting more difficult to control in grazing livestock as the parasites develop resistance to commonly used medications.

These gastrointestinal parasites also cost producers money and resources by way of treatment and lost productivity. For example, internal parasites cost the Australian sheep industry around $400 million each year, with huge implications for animal welfare. The cattle and sheep industries in North America and other parts of the world face similar costs and lost performance.

The problem facing farmers is that most worm populations are now showing resistance to the drugs used, making it more and more difficult to cure infestations. This drug resistance is leading scientists with Australia's Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) to work with The University of Queensland’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience (IMB) to look for new treatments derived from the venom of spiders, scorpions and assassin bugs.

University of Queensland doctoral student Samantha Nixon is studying the effect of the venom on the barber’s pole worm (Haemonchus contortus). Although these worms are relatively small (3 cm in size) compared to tapeworms in sheep, which can be longer than 1 m, Nixon said it’s the sheer number of barber's pole worms that can overwhelm a sheep’s body.

“The number of adult worms in a sheep’s gut can be as high as 10,000, and these worms can actually drain 10% of the sheep’s blood each day. If that happened to you, you can imagine that you would feel very ill,” Nixon said.

This can quickly become a fatal spiral for a sheep’s health. They end up anaemic, malnourished and very weak and can rapidly lose weight. Sudden death can occur if the infection remains untreated.

“From an animal welfare perspective, these parasites are absolutely devastating. From a farmer’s perspective, the loss of productivity is huge. You have drastic reduction in the quality and quantity of wool and meat, which really hurts the industry,” she said.

The good news is that spider venoms contain powerful chemicals that could be used to fight these infections.

Venoms are an amazing untapped resource to look for potential drugs, having evolved over millions of years to deliver fine-tuned, potent and fast-acting chemicals.

Unfortunately though, drug discovery is a time-consuming process. It takes more than 10 years for the average drug to go through the process of discovery and testing before being released onto the market, CSIRO said.

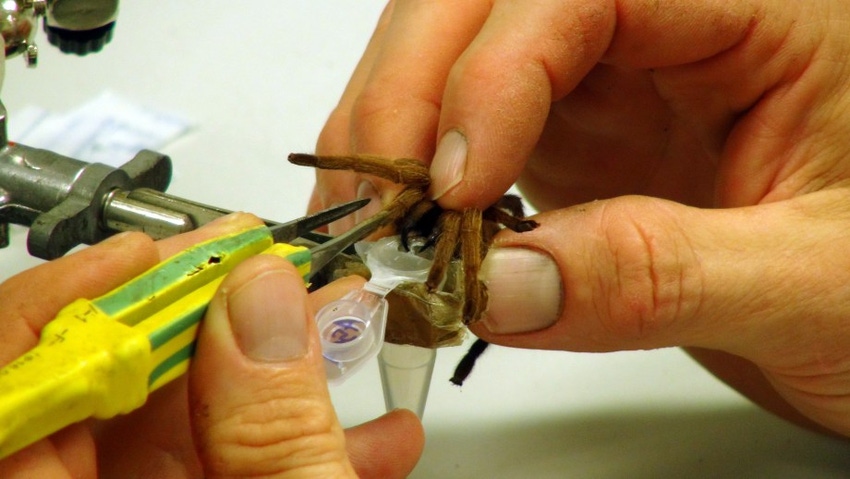

“First, we milk the venom and then purify it before testing the crude venom against the parasite. Then, we go back and forth between fractioning the venom and testing it to pick out the bioactive molecules,” Nixon said. “We’re looking to find individual molecules that work against the parasite, and only then can we start looking at how to produce them on a large scale.”

Farming venom out of animals like spiders isn’t feasible on a large scale, so to develop a cost-effective drug, scientists would need to create a similar molecule at mass scale using methods like protein expression. The hope is that such a drug would be effective against multiple types of parasites, not just the barber’s pole worm in sheep. The drug might also be effective in other livestock like cattle and even in people.

“When we find potential drug candidates, we will collaborate with researchers around the world to look for new ways they could be used. We want to make a genuine difference in the lives of people and animals affected by parasitic diseases,” Nixon said.

Nixon's current doctoral program follows similar work she did at the University of Queensland while completing an honors program in biomedical science.

Superbugs and cancer

Indeed, other researchers are also looking at arachnids for new compounds to treat antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and cancer.

One area of focus is antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which could someday be an alternative to currently prescribed antibiotics, many of which are becoming increasingly useless against some bacteria. Another IMB research team recently reported in ACS Chemical Biology that they have improved the antimicrobial — and anti-cancer — properties of an AMP from a spider.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2 million people become infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the U.S. each year. Researchers are trying to find alternatives to traditional antibiotics, and one such possibility is a group of peptides called AMPs. These peptides are found in all plants and animals as a type of immune response and have been shown to be potent antibiotics in the laboratory.

Gomesin, an AMP from the Brazilian spider Acanthoscurria gomesiana, can function as an antibiotic, but it also has anti-cancer activity. When gomesin was synthesized as a circle instead of as a linear structure, these characteristics were enhanced. Sónia Troeira Henriques and IMB colleagues wanted to further boost the peptide's traits.

The team made several variations of the cyclic gomesin peptide and found that some of these were 10 times better at killing most bacteria than the previously reported cyclic form. In other experiments, the new AMPs specifically killed melanoma and leukemia cells, but not breast, gastric, cervical or epithelial cancer cells.

The Australian researchers determined that the modified peptides killed bacteria and cancer cells in a similar way — by disrupting the cells' membranes. The group also noted that the modified AMPs were not toxic to healthy blood cells.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like