Video games offer clues to help curb animal disease outbreaks

Vermont research shows how farmers’ risk attitudes affect spread of infectious animal diseases and offers first-of-its kind model for testing disease control and prevention strategies.

June 25, 2019

Strengthening biosecurity is widely considered the best strategy to reduce the devastating impact of disease outbreaks in the multibillion-dollar global swine industry, but successfully doing so all comes down to human decision-making, a University of Vermont study shows.

The study, published June 25 in Frontiers in Veterinary Science, is the first of its kind to include human behavior in infectious disease outbreak projections — a critical element that has largely been ignored in previous epidemiological models, the university said.

Incorporating theories of behavior change, communications and economic decision-making into disease models gives a more accurate depiction of how outbreak scenarios play out in the real world to better inform prevention and control strategies, the announcement said.

“We’ve come to realize that human decisions are critical to this picture,” said Gabriela Bucini, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Vermont department of plant and soil science and lead author of the study. “We are talking about incredibly virulent diseases that can be transmitted in tiny amounts of feed and manure. Ultimately, controlling these diseases is up to the people in the production system who decide whether or not to invest and comply with biosecurity practices.”

Seeking to understand the role of human behavior in animal disease outbreaks, the researchers designed a series of video games in which players assumed the roles of hog farmers and were required to make risk management decisions in different situations, the announcement said. Observing how players responded to various biosecurity threats provided data used to simulate the spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) — one of the most severe infectious diseases in the U.S. swine industry — in a regional, real-world hog production system.

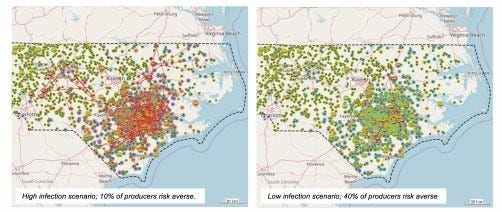

The number of pigs that contracted PEDV was shown to be highly dependent on the risk attitudes of the farmers and producers in the system, and a relatively small shift in risk attitudes could have a significant impact on disease incidence, the researchers said.

According to the study, getting just 10% of risk-tolerant farmers to adopt a risk-averse position with stronger biosecurity measures reduced the total incidence of PEDV by 19%. Keeping the disease under control required at least 40% of risk takers to change their attitudes.

“The risk attitudes and human decisions that we’re incorporating in the model are really powerful,” said Scott Merrill, co-author and researcher in the department of plant and soil science and Gund Institute for the Environment. “If we can change the way people behave, then we have a chance to make some dramatic impacts and avoid a devastating outbreak.”

Getting serious about games

Merrill and Bucini are part of a team of researchers in the University of Vermont's Social Ecological Gaming & Simulation (SEGS) Lab who are designing interactive “serious” games and computational models to understand complex systems.

Developed by Merrill, along with Chris Koliba and Asim Zia in the department of community development and applied Economics and Gund Institute for the Environment, the SEGS Lab places research subjects in a virtual world where researchers can monitor their behavior — an approach that may help eliminate some of the biases that can occur with traditional surveys.

Their work in the area of animal disease biosecurity is part of a $7.4 million, multi-institutional biosecurity initiative led by University of Vermont animal science researcher Julie Smith that’s aiming to inform policies that collectively reduce the impact of pests and diseases on food-producing livestock in the U.S., the university explained in its announcement.

The PEDV outbreak model is grounded in data derived from the biosecurity video games, which found that people behaved differently depending on the type of information they received and how it was presented. In one game, players were given several different risk scenarios and had to decide whether to maximize their profit or minimize their risk. Players presented with a 5% risk of their animals getting sick if they ignored biosecurity protocols complied only 30% of the time. However, when the risk level was presented visually as “low risk” on a threat gauge with some built-in uncertainty, rather than numerically, players complied more than 80% of the time, the researchers said.

“A simple thing like going out the wrong barn door can have a huge impact,” Merrill said. “With the game data, we can see big differences in the economic and disease dynamics as we change the type of information we’re delivering and the way it’s delivered.”

Rising global threat

Infectious diseases like PEDV pose a continuous risk to U.S. hog producers -- one that is increasing with the consolidation and globalization of the industry, the university said. The diseases are highly contagious, and the effects can be catastrophic. PEDV was first detected in the U.S. in 2013. Within one year, it spread to 33 states and wiped out as many as 7 million pigs, or 10% of the nation’s agricultural swine population.

Since then, U.S. producers have ramped up biosecurity measures, but PEDV remains endemic in the U.S., and new and emerging pests and diseases are on the rise. An ongoing outbreak of African swine fever in Asia has decimated pig herds across China, the world’s largest consumer of pork, and pork prices are expected to hit record levels in 2019.

“Biosecurity efforts are often voluntary but are critical to prevention, especially when there are no vaccines or treatments available,” said Smith, principal investigator of the animal disease biosecurity project. “We have to understand where people are on the risk continuum, their barriers and challenges and their ability to act. That information is critical to the response.”

The Animal Disease Biosecurity Coordinated Agriculture Project is funded with a National Institute of Food & Agriculture grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2015-69004-23273. Collaborating research and extension faculty are based at the University of Central Florida, Iowa State University, Kansas State University, Montana State University and Washington State University.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)