Sensor can 'smell' spoiled milk before opening

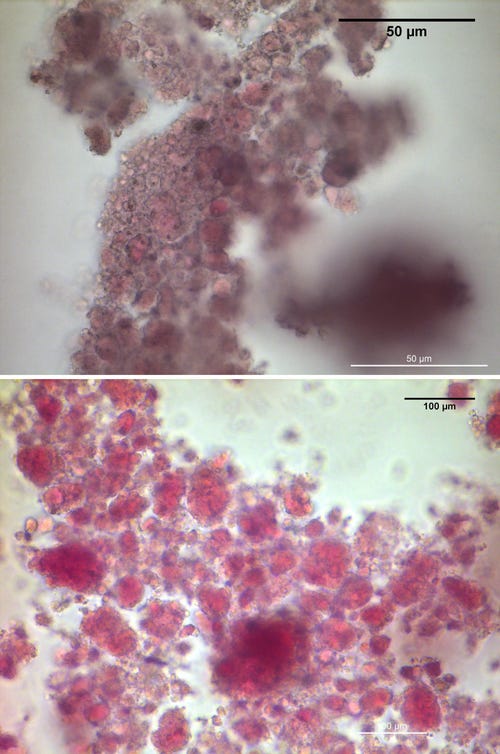

Sensor consists of chemically coated nanoparticles that react to gas produced by milk and bacterial growth that indicates spoilage.

May 8, 2019

Expiration dates on milk could eventually become a thing of the past using new sensor technology from Washington State University scientists.

Researchers from the department of biological systems engineering, the School of Food Science and other departments have developed a sensor that can "smell" if milk is still good or has gone bad.

"If it's going bad, most food produces a volatile compound that doesn't smell good," Sablani said. "That comes from bacterial growth in the food, most of the time, but you can't smell that until you open the container."

The sensor detects these volatile gases and changes color. The breakthrough is in the early stages, but Sablani and his colleagues showed in a paper published in the journal Food Control that their chemical reaction works in a controlled lab environment.

The next step for the team is developing a way to visually show how long a product has before it spoils. Currently, the sensor only shows if milk is okay or spoiled.

Although still early, Sablani envisions working with the food industry to integrate his sensor into a milk bottle's plastic cap so consumers can easily see how much longer the product will stay fresh.

One problem with current expiration dates is they are based on best-case scenarios. "The expiration date on cold or frozen products is only accurate if it has been stored at the correct temperature the entire time," Sablani explained.

Temperature abuse — or the time a product has spent above refrigerator temperature — is very common, he said. It can happen during shipment or if a consumer gets delayed on the way home from the store.

"We'll have to work with the industry to make this work, but we're confident that we can succeed and help improve food safety and shelf life for consumers," Sablani said.

Source: Washington State University, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like