Minnesota Fed projects more farm stress ahead

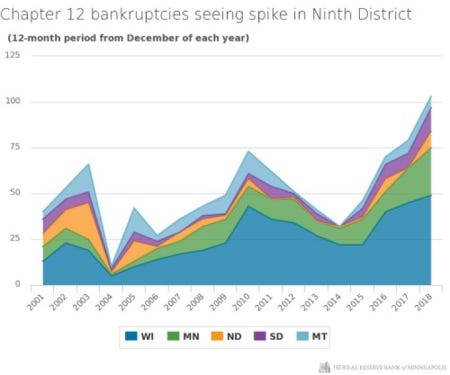

Chapter 12 bankruptcies nearly three times what they were in 2014 as farms struggle with big supplies and dampened prices.

Not surprisingly, another year of low prices is compounding stress among farmers, according to Ronald Wirtz, director of regional outreach at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Minn.

“The Ninth District’s farm economy might generously be described as struggling to tread water,” Wirtz said. He noted that the blame is mostly low prices, which have fallen significantly from levels seen from 2011 to 2013. However, farmers are also a victim of their own success in producing higher yields without matching increased demand to the higher supplies.

Tariffs have created some trade-induced interruptions in international demand for U.S. commodities as well.

Wirtz reported that Chapter 12 bankruptcies in the Ninth District, which includes Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana, have increased steeply since 2014. Over the 12 months ending in June 2018, 84 farm operations in Ninth District states had filed for chapter 12 bankruptcy protection — more than twice the level seen in June 2014. For the 12 months ending in December 2018, 103 Chapter 12 bankruptcies were filed. For comparison, that's nearly three times as many as in 2014.

Bankruptcies are rising in all district states but are particularly pronounced in Wisconsin, more notably in the western half of the state. In November 2018, Wirtz said Wisconsin accounted for about 60% of all bankruptcies among Ninth District states. “Anecdotal evidence suggests that the state’s smaller average farm size, particularly in dairy, is at least part of the reason for the uptick,” Wirtz said. The average dairy herd in Wisconsin is still just 153 cows; in California, the average herd is 1,300 cows.

Wirtz added that there about 260 agricultural banks in the Ninth District, and while conditions have deteriorated some, most metrics suggest that the banks are still in decent shape. Loan demand was also predicted to go up, which could be considered a good thing for bankers, except that credit quality was expected to deteriorate given low commodity prices and falling farm incomes. As a result, more banks are seeking higher collateral rates for ag loans.

“And, in a cruel twist, extreme winter weather and heavy snowfall have led to the collapse of or damage to hundreds of barns and other farm buildings, along with further damage to equipment and the loss of livestock. The subsequent spring thaw has compounded matters with floods across much of the district, with further losses of livestock, buildings and machinery,” Wirtz said.

Minnesota takes deep hits

After adjusting for inflation, Minnesota farms earned the lowest median farm income in the past 23 years of data tracked by the University of Minnesota Extension and agricultural Centers of Excellence within Minnesota State.

In 2018, the reported median net income was $26,055, down 8% from the previous year. Farmers in the lowest 20% reported losing nearly $72,000. The analysis examined data from 2,209 participants in farm business management programs as well as 101 members of the Southwest Minnesota Farm Business Management Assn.

“We don’t have consistent numbers that go back that far, but it is very likely that 2018 was the lowest income year for Minnesota farms since the early 1980s,” said Dale Nordquist of the Center for Farm Financial Management at the University of Minnesota. “That said, the previous five years were not much better, so many Minnesota farms have had a string of low-income years, and that has both financial and emotional impacts.”

The economic pain is widespread. The median producer in all four of Minnesota’s primary agricultural products earned net farm income of less than $31,000.

However, on a more positive note, farm balance sheets did not deteriorate substantially from previous years. The average farm’s debt-to-asset ratio increased slightly to 36%, which is still a relatively strong financial position largely supported by farmland that has maintained its value. When non-farm earnings are added to the picture, the average farm family’s net worth increased by almost $30,000.

Dairy farms have been particularly hard hit by low prices in recent years. Overproduction and trade issues have weighed on milk prices, causing many dairy farms to sell their herds. In 2018, the median dairy farm in these farm management programs earned less than $15,000, down from $43,000 in 2017. Milk prices were down 7% in 2018 — and down 33% from their highs in 2014.

Nate Converse, Central Lakes College farm business management instructor, said it has been difficult for many dairy farmers. “As a result, many of them have decided they can’t wait for things to turn around,” he said.

In 2017, the pork industry was the one bright spot in Minnesota agriculture, but in 2018, the median pork producer earned only $27,739, down from more than $101,000 in the previous year. Pork prices were down 9%, again largely affected by trade issues. The average hog finisher lost $11.50 per head sent to market.

Low profits continued for beef producers. The median beef participating beef farm earned just over $6,000, virtually unchanged from the very low profitability of the previous year. Beef finishers lost almost $30 per head marketed.

Not every operation struggled. Across all farms, the farms earning the highest net incomes — those in the top 20% — earned an average of $184,000.

Across all farms in Minnesota, the University of Minnesota reported, 34% lost money on their farming operations in 2018, 40% lost net worth after family living expenses and taxes and 53% lost working capital. Josh Tjosaas, Northland Community & Technical College farm business management instructor, said, “The working capital picture would have been worse, but many farms were forced to restructure debt, moving short-term debt down the balance sheet and securing it with land and other collateral."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like