Engineers develop bury-and-forget sensors, data networks for better soil, water quality

Sensor data could help build better models of interactions of fertilizer, soil and crops.

November 6, 2018

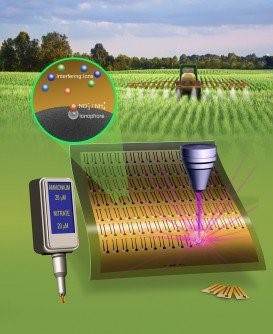

Engineers at Iowa State University and the University of Florida are working on a new system of “bury-and-forget” soil sensors and remote, wireless, data collection networks that could help reduce fertilizer runoff that can feed algae blooms or contribute to the “dead zone” of oxygen-depleted water in the Gulf of Mexico along the Louisiana coast.

The runoff reduction and healthy soil system envisioned by the engineers could help reduce the runoff of nitrogen fertilizer by using data from the sensors to build better models of the interactions among fertilizer, soil and crops. Those models could help farmers reduce the amount of fertilizer they use.

Currently, farmers test for soil nutrients by taking soil samples and sending them to a laboratory for analysis, which can be a slow, expensive and imprecise process.

“If we had a better predictive model, we could have better remedies for farmers,” said project leader Jonathan Claussen, an Iowa State assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “A better model could tell them they can use less fertilizer.”

The project is supported by a two-year, $300,000 “Signals in the Soil” grant from the National Science Foundation. The engineers hope to collect enough data and demonstrate enough potential to successfully compete for more funding and additional research.

In addition to Claussen, the research team includes three engineers from the University of Florida in Gainesville: William Eisenstadt, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and Melanie Correll and Eric McLamore, both associate professors of agricultural and biological engineering.

Claussen has expertise in developing low-cost, flexible sensors based on inkjet-printed and laser-treated graphene circuits. The sensors in this project will detect ammonium and nitrate ions in soil. Claussen said he hopes they will work for an entire growing season.

Eisenstadt has expertise in electronics and wireless sensor systems; Correll has expertise in crop modeling, including soil biochemistry, and McLamore has expertise in environmental/agricultural chemistry as well as biosensors.

The engineers will build the sensors, connect them to a wireless network, test how deep the sensors can be buried while maintaining network connections, build a test bed facility using tomato plants as a model crop and collect high-resolution nitrogen data from the soil while monitoring plant growth.

“Such sensor networks and resultant models are expected to lead to precision agriculture where fertilizers are spread onto specific locations of the field in a metered fashion and only when needed,” the researchers wrote in a summary of their project.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)