Collaboration seeks to make developing new dairy ingredients with specific functional properties easier.

February 18, 2016

A collaboration between South Dakota State University (SDSU) dairy scientists and chemical engineers in Australia will make it easier to develop new dairy ingredients with specific functional properties.

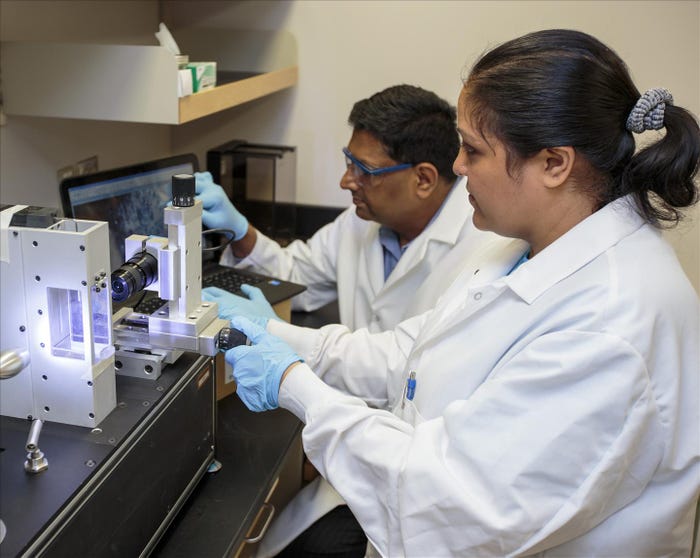

SDSU dairy researchers are using a bench-scale single-droplet spray dryer to determine the exact drying parameters for an ingredient with the desired functional properties.

Associate professor Cordelia Selomulya and her team at Monash University near Melbourne, Australia, then will utilize the data on drying behavior of different materials to develop a computational fluid dynamics model to predict the range of drying parameters needed to produce a powder with those properties in a spray dryer.

Doctoral student Hiral Vora, right, works on the single-droplet spray dryer. Credit: South Dakota State University.

"Our expertise is in manufacturing and functionality; theirs is in engineering and modeling," professor Lloyd Metzger, who leads the SDSU research team, said. "It's an ideal collaboration because our areas of expertise are complementary."

The project was begun by former assistant professor Hasmukh Patel, who is now a senior principal scientist at Land O’Lakes in Minneapolis, Minn.

The SDSU portion of the three-year project, which began in 2014, is supported by a Dairy Management Inc. grant of more than $250,000. The research focuses on optimizing spray-drying conditions for milk powders and dairy ingredients such as whole milk powder, whey and milk protein concentrates and isolates and infant formula.

Doctoral student Hiral Vora and other SDSU dairy science staff are working on the project.

Determining desired properties

When it comes to spray-drying, any number of conditions can affect powder properties, including the characteristics of the material being dried, the nozzle type, the amount of pressure behind nozzle, the fluid preheat temperature and the air inlet and outlet temperature, according to Metzger.

Additionally, the desired powder properties will vary for different products. For instance, in an application like coffee creamer, the powder must dissolve very quickly in hot coffee, he pointed out, and it may be required to foam. In other applications like infant formula, the density of the powder is critical to ensure that each scoop of powder has the correct nutrient content.

The dairy industry now uses trial and error or past experience to adjust drying conditions to achieve the desired powder characteristics, Metzger explained.

This approach assumes that what happens with a small batch using a lab-scale or pilot-scale dryer will work on a larger scale, according to Selomulya. However, she cautioned, "both are complex systems in their own right, so the drying history will be different for each dryer. With the variation of feed formulation in dairy, trial and error is not an effective approach."

Developing predictive model

Selomulya and her team will calculate the drying rate of the material using experimental data, such as changes in mass, droplet temperature and size, along with morphological changes — such as skin formation — from the single-droplet dryer, combined with a reaction engineering modeling approach. The results will then be used in a computational fluid dynamics model to predict what will happen inside an industrial spray dryer.

"It's all about trying to simulate on a small scale with the single-particle dryer and relate that to what happens in the big dryer," Metzger said. The semicommercial-scale dryer at the Davis Dairy Plant at SDSU will be used to validate the methodology and scale up the models developed.

This collaborative effort promises to streamline the process of changing formulations and developing new dairy ingredients — and that could translate into huge savings for the dairy industry.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)