Knowing what factors may lead to poor-quality or contaminated forages and feed ingredients can be best means to develop plan to negate those challenges.

June 12, 2019

Ash, molds, toxins, yeasts and negative bacteria — the list of anti-nutritional factors that are challenging this year’s forage is getting lengthy, according to Rock River Laboratory in Wisconsin.

Moisture to date in 2019 has created a perfect storm for ill-fated forage harvests, in addition to historically delayed planting of crops, but instead of assuming doom and gloom, an assessment of the contributors involved can help shed light on realigning the plans for this year’s forage to negate or reduce the anti-nutritional factors that are lurking, Rock River Laboratory said.

“We see water-logged fields that have serious potential for high ash content,” Rock River Laboratory animal nutrition, research and innovation director Dr. John Goeser explained. “Those preparing their hay with additionally required merging, raking and tedding due to wet conditions may be unknowingly helping this potential come to life.”

Goeser said wet fields carry a number of opportunities for ash (soil contamination). “Tires pick up mud, tines hit the ground and kick up mud or soil and rainfall has already potentially splashed added soil up onto standing plants,” he said -- not to mention that the flooding seen across the U.S. leaves silt and soil on standing plants, if they haven’t died already.

“All of this additional cellular rainwater can further activate and potentially carry bad bacteria, mold and yeast into and around forage,” Goeser said. “Rain drives fungi from the soil and ash onto standing or cut plants, and these microorganisms are then better able to grow in these types of moist environments.”

Optimal fermentation is trump card

Despite all of the vectors for disaster to arise, there are ways to mitigate the risks involved with these feed hygiene challenges, Rock River Laboratory said.

“Harvesting the crop at the right moisture is going to be all that more critical,” Goeser said. “If farmers are forced to decide between the right moisture and the forage getting rained on post-cutting, I recommend chopping it wetter to avoid a rain event this year.”

Rain on forages prolongs drying, leading to low sugars in the plant and requiring more management like raking and tedding that tends to increase ash contamination. By avoiding rain, forage has a better chance of fermenting, to some extent, to mitigate any hygienic caveats.

“The right bacteria and sugar present, plus correct packing, is highly important to fermentation,” Goeser emphasized. “Pour a research-backed inoculant on it at potentially greater rates than typical, separate it from other forages, avoid blending it with past year forages, utilize good fermentation management practices and feed it sooner than later.”

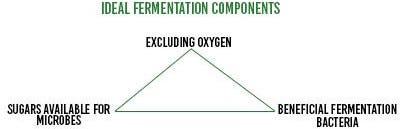

What are good fermentation management practices? Ideal fermentations require a few key ingredients: exclusion of oxygen, the presence of a beneficial fermentation bacterial population (for example, inoculant) and available sugars for the microbes to work (Figure).

“If any of these factors are compromised or forage has been heavily rained on over a quarter of an inch, the use of acid products can be an alternative for those ingredients,” Goeser said.

Balance for quality

Forage quality is key every year, but especially in years when forage inventories may come up short. “Harvesting forage at the highest quality possible, considering the conditions, is really important,” Goeser said. “If the first crop fell short, try to hit the best second, third and fourth cuts to make up the quality.”

To assess quality, Goeser recommended walking fields, utilizing a PEAQ stick with the first cut and scissor clippings with later cuts and having managers who can help. “Pull together your consultant team, and get them talking to discuss the current status and optimizing quality; that includes your nutritionist and agronomist.”

Despite these recommendations, many can attest to the fact that forage harvest and planting have been tricky in 2019. “I know we’re eager to get in the fields to get hay off so we can plant corn,” Goeser said, but on the other hand, “we don’t want to destroy the soil structure within the fields — especially with the winter kill — unless we’re taking off alfalfa to plant corn.”

Commodity protection

While current forages are the priority when it comes to preventing or mitigating the challenges from anti-nutritional factors, on-farm commodities are also susceptible to these same risks.

“Commodities in bays have been flooded with rain, which can wreak havoc on their quality,” Goeser explained. He recommended completely cleaning out commodity facilities between low supplies and new shipments, as opposed to dumping it in front of the old contaminated commodities. He added that producers should “proactively ensure the next delivery isn’t contaminated to start on the right foot.”

While 2019 may be an extension of last year’s forage woes, albeit in a slightly different fashion, producers now are better equipped and informed to proceed proactively.

Knowing what factors begin a chain of events that lead to poor-quality or contaminated forages can be the best means to outline a plan to negate those challenges. As Goeser recommended, “assess quality, discuss with your consultant team and work toward an optimal fermentation to avoid fermentation and feed cleanliness issues in 2019.”

Founded in 1976, Rock River Laboratory is a family-owned laboratory network that provides production assistance to the agriculture industry through the use of advanced diagnostic systems, progressive techniques and research-supported analyses.

You May Also Like