Method eliminates lengthy process of separating compounds and lowers testing costs while providing high sensitivity and accuracy.

February 25, 2020

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) Crop Development Center (CDC) have developed a fast and accurate method for identifying and quantifying toxins in fusarium-infected cereal grain -- an innovation that could reduce toxins that are harmful to both animals and people, the university said in an announcement.

With warming weather patterns and more intensive farming practices, fusarium has been spreading across the prairie provinces of Canada, USask said. The infected grain is often both lower in quality and kernel weight and may be unsuitable for human and animal consumption.

That’s because the fusarium infection process produces mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol (DON), which, in severe cases, can reduce the market value of a crop to zero. Animals consuming feed containing high levels of DON may have reduced growth as well as reduced fertility and reduced immune response, USask said.

Because mycotoxins such as DON are not destroyed during processing such as milling, baking or malting, testing infected feed grain for the concentration of DON is becoming critically important, USask noted. To limit mycotoxins in food and feed, regulations specify maximum allowable concentrations, and if these limits are exceeded, products cannot be sold.

Breeding for low DON concentration in cereal crops is an important control measure for the disease, CDC research officer Lipu Wang said.

“The problem has been that crop breeders and researchers have lacked a way to measure DON that is both quick and accurate,” Wang said.

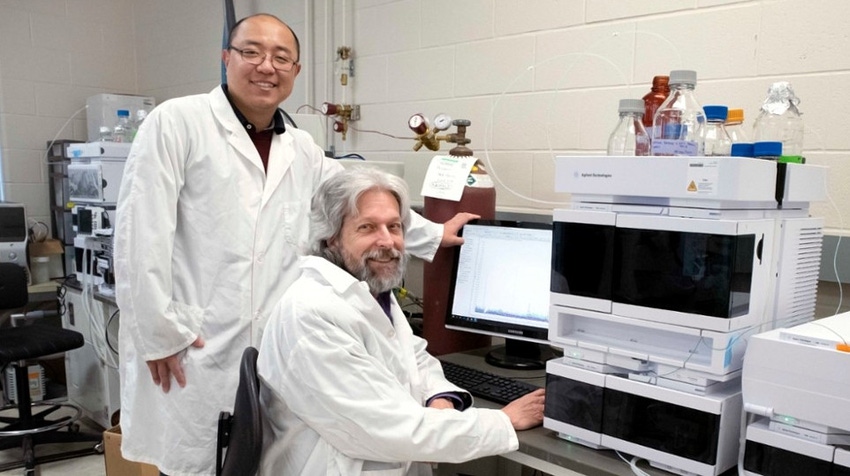

Wang and USask researcher Randy Kutcher of the CDC’s cereal and flax pathology program have come up with a new way to test for DON that involves a one-step extraction of the mycotoxins using the chemical solvent acetonitrile, followed by direct injection of the toxins into a mass spectrometer to identify and quantify them. This method eliminates the lengthy process of separating the compounds and lowers the cost while providing high sensitivity and accuracy compared to other methods, USask said.

“Analysis that previously took 20 minutes per sample can now be done in less than two minutes, which is very important when testing thousands of samples,” Wang said. “This new method offers breeders a much more efficient way to select wheat or barley lines that accumulate less DON.”

Eventual use of the new method by grain companies has the potential to enhance quality assurance for the grain industry in domestic and export markets, Kutcher added.

“Our customers want no contaminants — no toxins — in our grain,” Kutcher said. “It may also help in deciding whether grain should be processed as food or animal feed.”

The research team is now using the new mycotoxin test in the plant pathology program at the CDC and using the mass spectrometer in the USask College of Pharmacy & Nutrition. They are seeking to expand the diagnostic testing with research collaborators, interested breeders and clients, the announcement said.

The team has also developed a way to identify and quantify other toxins, providing a powerful tool to detect new types of mycotoxins in newly developed cereal grain varieties, USask added.

The project is supported by the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund and the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)