Work with condensed tannins puts lab on global map for focus on vegetation like forbs and dicots that naturally address internal parasites detrimental to ruminants.

February 2, 2017

The Forage & Ruminant Nutrition Lab at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research & Extension Center in Stephenville, Texas, explores ways to improve ruminant diets and mitigate the negative environmental impacts for researchers around the state, nation and globe, according to Dr. Jim Muir, a Texas A&M AgriLife Research expert.

Muir, an AgriLife Research grassland ecologist based in Stephenville, said the lab is used by researchers throughout Texas, the southeastern U.S. and as far away as South Africa, Brazil and Argentina. The lab analyzes soils and manure to determine mineral content and forages to measure digestibility and nutritional quality of what livestock are consuming or might consume, he said.

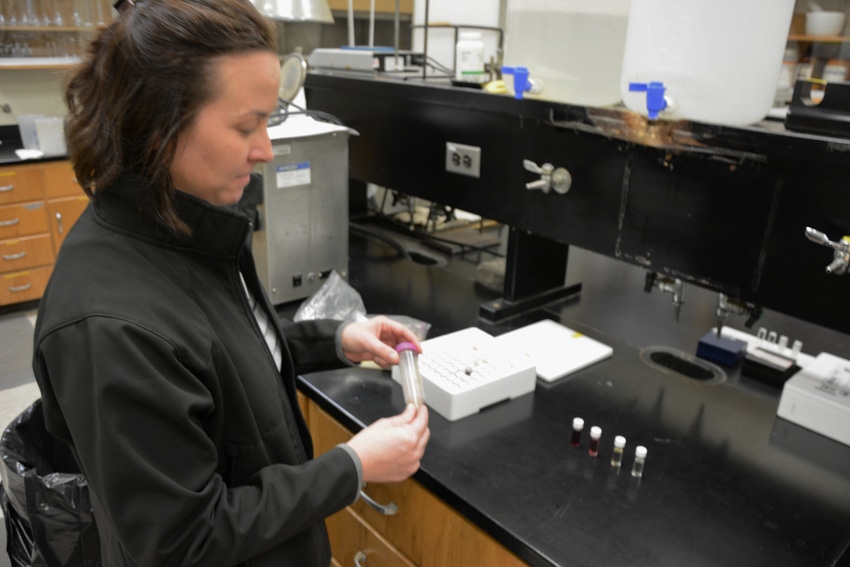

Nichole Cherry, an AgriLife Research associate, is the person who makes the lab run, Muir said. During her 13 years in the lab, Cherry has performed more than 100,000 assays on samples to determine various aspects of forage and soil composition — from the digestibility of forages to condensed tannin levels to identifying elements and compounds within samples.

For example, Muir said Cherry uses a machine that emulates an animal’s digestive system. It can predict digestibility in just hours — something that would take up to six weeks by testing animals in pastures or feedlots. The machine can analyze 50 samples in 48 hours.

“We can predict the effects and digestibility of anything the animal might ingest,” Muir said.

The majority of the lab’s work is on small ruminants such as sheep and goats, which are more popular globally, and some white-tailed deer, Muir said. About 60-70% of samples sent in by researchers serving producers are small ruminants.

Cherry’s work with condensed tannins has put the lab on the global map because it focuses on vegetation like forbs and dicots that naturally address internal parasites that can be deadly to ruminants, Muir said.

Parasites are especially rampant in tropical regions where rainfall and warm temperatures are prevalent, he said. In Texas, springtime and over-grazed pastures present parasite challenges for producers. Muir said condensed tannins are a natural tool for producers who hope to mitigate losses to parasites.

“Condensed tannins evolved in plants as a way to protect themselves,” he said. “It usually makes them bitter and less palatable or poisonous to animals or insects, but some animals have harnessed their protective features in a co-evolutionary relationship.”

Tannins can be good and bad for animals, so the lab tries to identify ratios to help producers decide whether to increase or reduce certain browse, such as woody plants and shrubs, in the animals' diets, especially for browsers such as goats and white-tailed deer, Muir said.

Tests can determine the level of condensed tannins, where they are in the plant cell, how they are delivered and break down in the animal’s digestive tract or how biologically aggressive they are in fighting gastrointestinal parasites.

Condensed tannin assays take about two weeks, Muir said, adding that without Cherry and the Forage & Ruminant Nutrition Lab, “our research program on small ruminant gastrointestinal parasites, such as barberpole worm, would not exist. Producers in Texas, the southeastern U.S. and many corners of the world depend on her assays to keep their animals healthy and increase their profits.”

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)