Much of Southeast and Texas in grip of drought, so university experts offer producers advice to manage their livestock and forages.

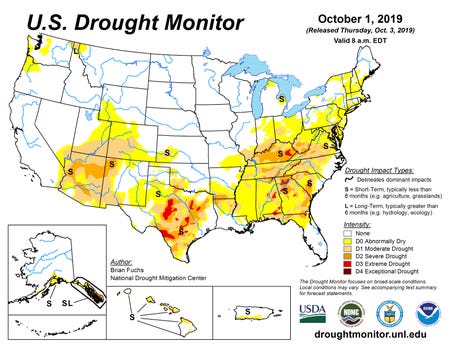

While producers in the Midwest and Corn Belt have been dealing with a wet fall, drought conditions have taken over much of the Southeast and Texas, according to the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor map released Oct. 1.

Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service area livestock and forage agent Lee Van Vlake said making proper management decisions can help cattle producers lessen the effects of drought on their operations.

“Drought conditions can have severe impacts on cattle, but if certain strategies are in place, this can help minimize the economic impact,” Van Vlake said.

A decrease in forage availability is one of the most noticeable impacts of drought, he said. When this happens, producers are faced with the decision to supplement feed and purchase stored forage, which can increase production costs.

In Kentucky, more than half of the state is in the severe drought category, and some areas of southeastern Kentucky have moved into the extreme category, the University of Kentucky said, pointing to data from the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“This is the first time since 2016 that any portion of the state has been placed under the extreme category,” said Matthew Dixon, agricultural meteorologist for the University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food & Environment. “Impacts on the agricultural side are numerous, and unfortunately, we’ll start seeing some longer-term impacts of this drought.”

Clemson Extension beef specialist and Livestock & Forage Program team leader Matthew Burns added that cattle owners should have their hay tested (for both quality and potential toxicity problems), especially during drought situations, when nitrate poisoning can be of concern on some drought-stressed forages.

“Testing hay will allow producers to make sure they are meeting the nutritional needs of their cow herd through hay and supplementation, if needed,” Burns said. “If it is found that a herd needs supplements added to its diet, producers can work with their local Extension agent to determine a plan that works for their individual operation.”

When a drought strikes, animals should be organized into feeding groups based on nutritional needs by age and stage of production. Hay test results can be used to determine which forage to match with which group and which group needs more supplementation, Burns noted.

Lindsey Craig, Clemson Extension livestock and forage agent, said in times of stress, cattle owners are encouraged to designate parts of their pastures as “sacrifice pastures” for feeding locations for cattle.

“Having some sacrifice pastures available to protect forage from over-grazing across the entire farm is a good management practice when drought conditions are present,” Craig said. “Doing this will increase forage recovery and decrease forage recovery time when drought conditions subside.”

Once rain becomes steady again, pastures should be evaluated for forage growth, Craig said, adding, “Producers should only turn livestock back into the pastures after these pastures have shown adequate forage growth.”

Feeding cattle hay and other supplements may be expensive and can cost twice as much or more than delivering the same nutrients from a pasture. Brian Bolt, Clemson livestock specialist, encourages producers to investigate strategies to reduce waste.

“For example, use of a hay ring for round hay bales has been shown to reduce waste from 45% to just 7%,” Bolt said.

Stockpiling fescue or establishing winter annuals is important for pasture performance and persistence the following year. It is important for cattle producers to take time to stockpile fescue or ensure they have adequate growth of small grains so their forage supply won’t be adversely affected, he added.

�“Droughts are a reality,” Bolt said. “Producers should develop drought management strategies and plans that outline what steps will be taken to mitigate the effects well in advance. These include determining which animals will be culled first, where additional feed resources may be located and decision tools to evaluate their effectiveness at meeting animals’ needs.”

Forage producers in Kentucky are usually seeding new pastures and hayfields during early fall, and the cutoff date for dependable winter survival is Oct. 1 in average years, University of Kentucky extension forage specialist Ray Smith noted. This year, he said every day past that presents a bigger risk since the forecast is not favorable for adequate rainfall.

“It’s definitely too late for alfalfa,” he said. “Even some who seeded back in mid-August have seed just sitting in the field.”

Pasture conditions are not likely to improve, and hay will be short going into winter, Smith said. Farmers, who usually stockpile forages for the winter, haven’t been able to do that this year.

“If you don’t have sufficient hay supplies to get you through the winter, you need to line it up sooner than later,” Smith said. “The longer you wait, the more you’ll have to pay, if you can find it at all.”

Kentucky only averaged 0.28 in. of measurable rainfall for the month of September. It was the driest September on record, going back to 1895, and it will also go on record as one of the warmest, the university said.

The Clemson Livestock and Forages Team is compiling resources related to drought management, supplementation, tax implications, as well as other topics and will house this information on its website at www.clemson.edu/extension/livestock/index.html. Burns said this information is expected to be available soon.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)