Animal agriculture's vulnerability to contagious livestock diseases such as influenza has demonstrated near-term need for non-thermal plasma reactor.

April 10, 2019

Dangerous airborne viruses are rendered harmless on the fly when exposed to energetic, charged fragments of air molecules, according to research conducted at the University of Michigan.

The University Michigan engineers have measured the virus-killing speed and effectiveness of non-thermal plasmas — the ionized, or charged, particles that form around electrical discharges such as sparks, an announcement from the university said. A non-thermal plasma reactor was able to inactivate or remove 99.9% of a test virus from the airstream, with the vast majority due to inactivation, the researchers said.

Achieving these results in a fraction of a second within a stream of air holds promise for many applications where sterile air supplies are needed.

"The most difficult disease transmission route to guard against is airborne because we have relatively little to protect us when we breathe," University of Michigan research associate professor of civil and environmental engineering Herek Clack said.

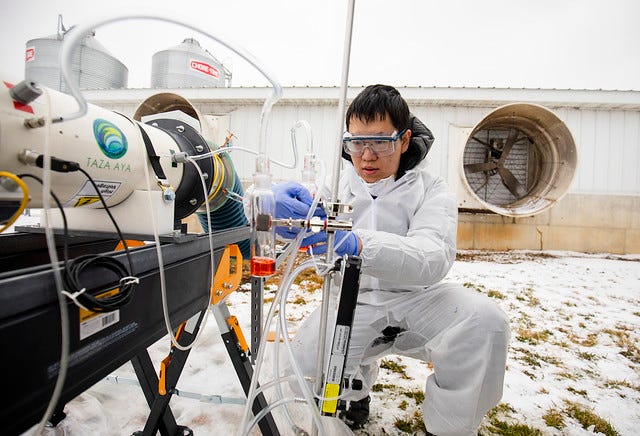

Clack and his research team have begun testing their reactor on ventilation airstreams at a livestock farm near Ann Arbor, Mich. Animal agriculture and its vulnerability to contagious livestock diseases such as avian influenza has a demonstrated near-term need for such technologies, the university said.

To gauge the effectiveness of non-thermal plasmas, researchers pumped a model virus — harmless to people — into flowing air as it entered a reactor. Inside the reactor, borosilicate glass beads were packed into a cylindrical shape, or bed. The viruses in the air flow through the spaces between the beads, and that's where they are inactivated, the researchers explained.

"In those void spaces, you're initiating sparks," Clack said. "By passing through the packed bed, pathogens in the airstream are oxidized by unstable atoms called radicals. What's left is a virus that has diminished ability to infect cells."

The experiment and its results were published in the Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics.

Notably, during these tests, the researchers also tracked the amount of viral genome that was present in the air. In this way, Clack and his team were able to determine that more than 99% of the air sterilizing effect was due to inactivating the virus that was present, with the remainder of the effect due to filtering the virus from the airstream.

"The results tell us that non-thermal plasma treatment is very effective at inactivating airborne viruses," said Krista Wigginton, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. "There are limited technologies for air disinfection, so this is an important finding."

This parallel approach — combining filtration and inactivation of airborne pathogens — could become a more efficient way of providing sterile air than technologies used today, such as filtration and ultraviolet light. Ultraviolet irradiation can't sterilize as quickly, as thoroughly or as compactly as non-thermal plasma, the researchers noted.

Source: University of Michigan, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)