Experimental tuber has potential to reduce disease in developing nations.

November 10, 2017

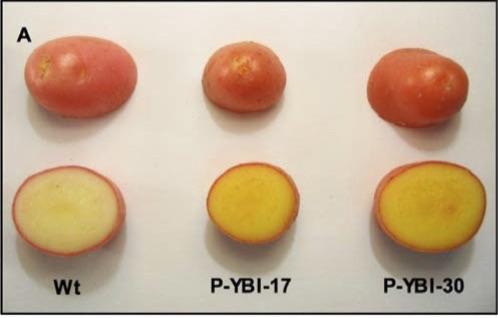

An experimental "golden" potato could hold the power to prevent disease and death in developing countries where residents rely heavily upon the starchy food for sustenance, according to new research.

A serving of the yellow-orange, lab-engineered potato has the potential to provide as much as 42% of a child's recommended daily intake of vitamin A and 34% of a child's recommended intake of vitamin E, according to a recent study co-led by researchers at The Ohio State University that appears in the journal PLOS ONE.

Women of reproductive age could get 15% of their recommended vitamin A and 17% of their recommended vitamin E from that same 5.3 oz. (150 g) serving, the researchers concluded.

Potato is the fourth-most widely consumed plant food by people after rice, wheat and corn, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It is a staple food in some parts of Asia, Africa and South America where there is a high incidence of vitamin A and vitamin E deficiencies.

"More than 800,000 people depend on the potato as their main source of energy, and many of these individuals are not consuming adequate amounts of these vital nutrients," said study author Mark Failla, professor emeritus of human nutrition at Ohio State and a member of its Foods for Health Discovery Theme. "These golden tubers have far more vitamin A and vitamin E than white potatoes, and that could make a significant difference in certain populations where deficiencies — and related diseases — are common."

Vitamin A is essential for vision, immunity, organ development, growth and reproductive health. Vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of preventable blindness in children. Vitamin E protects against oxidative stress and inflammation — conditions associated with damage to nerves, muscles, vision and the immune system.

In Failla's lab, researchers created a simulated digestive system that included a virtual mouth, stomach and small intestine to determine how much provitamin A and vitamin E could potentially be absorbed by someone who eats a golden potato. Provitamin A carotenoids are converted by enzymes into vitamin A that the body can use. Carotenoids are fat-soluble pigments that provide yellow, red and orange coloring to fruits and vegetables and are essential nutrients for animals and people.

"We ground up boiled golden potato and mimicked the conditions of these digestive organs to determine how much of these fat-soluble nutrients became biologically available," he said.

The main goal of the work was to examine provitamin A availability. The findings of the high content and availability of vitamin E in the golden potato were an unanticipated and pleasant surprise, Failla said.

The golden potato, which is not commercially available, was metabolically engineered in Italy by a team that collaborated with Failla on the study. The additional carotenoids in the tuber make it a more nutritionally dense food with the potential to improve the health of those who rely heavily upon potatoes for nourishment.

While plant scientists have had some success cross-breeding other plants for nutritional gain, Failla said the improved nutritional quality of the golden potato is only possible using metabolic engineering — the manipulation of plant genes in the lab.

While some object to this kind of work, the research team emphasized that this potato could eventually help prevent childhood blindness and illnesses and even the death of infants, children and mothers in developing nations.

"We have to keep an open mind, remembering that nutritional requirements differ in different countries and that our final goal is to provide safe, nutritious food to 9 billion people worldwide (by 2050)," said study co-author Giovanni Giuliano of the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy & Sustainable Development at the Casaccia Research Center in Rome, Italy.

Failla said "hidden hunger" — micronutrient deficiencies — has been a problem for decades in many developing countries because staple food crops were bred for high yield and pest resistance rather than nutritional quality.

"This golden potato would be a way to provide a much more nutritious food that people are eating many times a week or even several times a day," he said.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)