Economist says it's too premature to tell if markets have hit bottom from pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant falling cattle and hog prices linked to shifting demand and changes in the supply chain, Glynn Tonsor, Kansas State University Research & Extension agricultural economics professor and extension livestock market specialist, told participants via a new series of online gatherings, each focused on a different aspect of the virus’ impact on agriculture.

“Everybody, not just the ag and livestock sector, is adjusting to many things for the first time in their life in many ways. The [meat] supply chain is taxed, and that shows up in the marketplace, and even analysts and folks like me are taxed, so we’re doing our best,” Tonsor said.

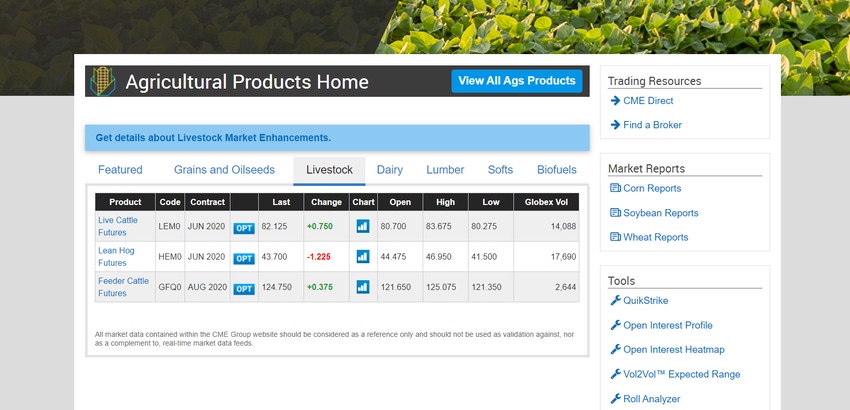

He noted that CME cattle and hog futures prices for April delivery have fallen 20-40% since Jan. 11, when the first death from COVID-19 was reported in China.

Live cattle futures for April delivery, for example, have fallen 29% -- from $127.96/cwt. on Jan. 10 to $91.00 on April 13. Hog futures plummeted 39% -- from $74.13/cwt to $44.90.

Cattle and hog futures for October delivery have also been down, Tonsor said, but not as significantly, indicating optimism that the agriculture sector will make adjustments between April and October.

U.S. meat demand is good during stronger economic times and weaker during poor economic times, he said, noting that beef demand, in particular, is “extra sensitive” to the macroeconomic environment, and it has become more so over time.

“That is particularly worrisome, because most folks who are macroeconomists think we have a weaker macroeconomic environment today than we did two months ago,” Tonsor said. “It’s pretty hard to argue that point.”

He noted that meat demand is shifting from foodservice to grocery demand. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, strong demand from institutional customers -- hotels, restaurants and schools -- helped drive prices. With schools across the country closed and restaurants reducing operations to curbside pickup or delivery only, demand has lessened for higher-priced meat cuts typically sought by restaurants but has increased for meat products typically bought in grocery stores, such as ground beef.

The difficulty, Tonsor said, is that “we raise whole animals, and we produce a lot of different products.” Some of the products traditionally go through primarily foodservice channels, and some go largely through retail, he noted.

“When we have a shock where one of those channels -- in this case, foodservice -- is closed off, it creates challenges to repurpose parts of the animal,” he said.

Tonsor gave the example of bacon, most of which typically goes through foodservice channels to restaurants rather than to consumer tables via grocery stories. Bacon is currently “stacking up” without that traditional primary outlet, which is a factor weighing on pork prices.

Tonsor launched a resource in February called the Monthly Meat Demand Monitor to help industry participants monitor consumer preferences, views and demand for meat. The tool is supported by checkoff funding from the beef and pork industries.

He noted that the temporary closure of several meat packing plants linked to COVID-19 is creating a bottleneck in the livestock supply chain.

“I think the industry is doing the best it can to deal with that, but it’s not surprising that this week we’ve had some unfortunate developments that are leading to slowdowns and temporary pauses in running some of our plants,” Tonsor said.

While no one plant represents more than 7% of national capacity, he said the challenge is that no one knows how many plants the virus will affect and for how long.

After crunching numbers for various beef cuts over the past several weeks, Tonsor said, “In aggregate, I think demand for beef is down, even though we’ve had a run on ground beef.”

Because there are so many unknowns about the pandemic, it’s unclear what the ultimate effect will be on the livestock market, Tonsor said. He and Iowa State University agricultural economist Lee Schulz recently hypothesized that that a 20% reduction in meat packing plant capacity because of COVID-19 would result in a 27% reduction in fed cattle prices and a 36% reduction in market hog prices.

Tonsor noted that the Livestock Marketing Information Center projected on April 3 that 2020 prices will be down because of the COVID-19 outbreak. However, Tonsor said the projections were more optimistic than the futures market suggests and believes that the projections likely have changed given news of temporary plant closures since those estimates came out.

Markets often operate like a pendulum, Tonsor said, but added that it’s premature to say markets have hit their bottom from the pandemic.

Longer term, he believes market disruptions will squeeze out some independent producers who did not have price protection in place and may also have an impact on how price reporting and price discovery occur.

“‘Populism’ was already growing before the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. and around the world, with people questioning the role of globalization,” he said. "Certainly, during [the COVID-19 outbreak], we have ramped up this discussion and action to improve domestic security, whether that’s on food, medical supplies or other supplies; there’s definitely a lot of effort in that space.”

If the current trend away from globalization of markets continues, he said this will mean less international trade.

“That would not be good for the U.S. ag sector. To support the size of the industry in the U.S., we need to sustain a presence in a global world,” Tonsor said.

Relationships, whether personal or financial, may be more important now than ever, he said, encouraging producers to reach out to their lenders, plus those they buy from or sell products to.

“I have full faith that we will adjust,” Tonsor said. “The U.S. is going to remain a very large ag producer. I’m not doomsday to that level. I have concerns that we’re in the midst of lots of shocks, but at the end of the day, in the aggregate, I remain optimistic for the industry and for society as a whole.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)