Currently, detecting and subtyping pathogens are separate processes, but new tool combines these two steps.

April 20, 2018

Quick, efficient pathogen detection and fingerprinting are essential and often lifesaving when it comes to preventing foodborne illness, and now, University of Georgia food scientist Xiangyu Deng has created a system that can identify foodborne pathogens much more quickly than traditional methods.

“In outbreaks, time is very important. When a pathogen is detected in food, we then have to determine its subtype, or fingerprint,” said Deng, an assistant professor of food microbiology at the University of Georgia Center for Food Safety in Griffin, Ga. “We need to shorten this process to the least amount of time possible.”

Currently, detecting and subtyping the pathogen are separate processes, but Deng has combined these two steps through a process called “metagenomics analysis.”

“To prevent a pathogen from spreading, you have to first identify it by studying its DNA signatures. Sometimes, you only have a few cells of the pathogen in a food sample -- just a tiny fraction of the resident microbial populations on the food,” he said. “You could sequence the entire sample (of food) to identify the pathogen inside it, but that would not give you enough pathogen DNA signal for identification.”

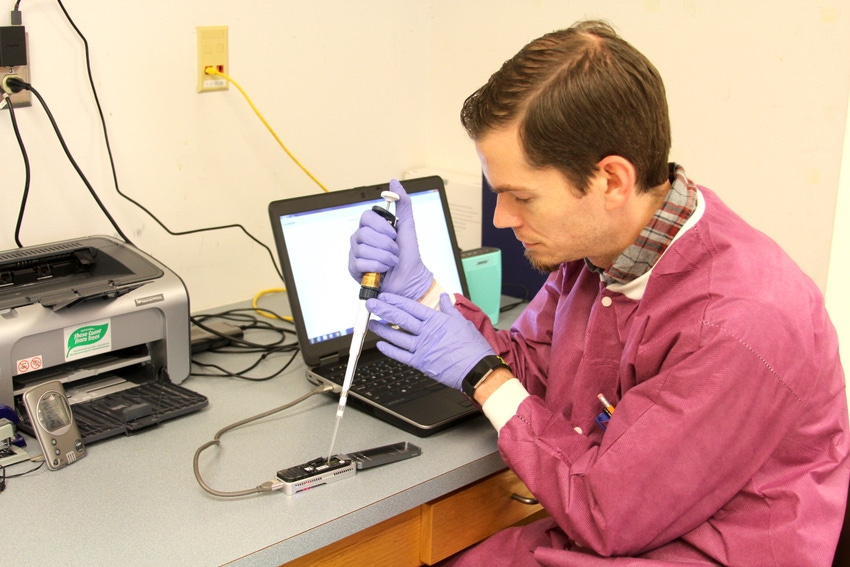

Traditionally, the pathogen is separated from the food sample by growing the pathogen in bacterial cultures, which takes 24-48 hours, Deng said. To shorten the culture process, researchers in Deng’s lab apply tiny magnetic beads coated with antibodies that pull out the pathogen cells. Then, they amplify the DNA of the captured pathogen cells so they have enough DNA to sequence.

“Using a new, very small sequencing tool that’s about the size of a USB drive, we can sequence while capturing the data in real time,” Deng said.

Compared to the mainstream genome sequencer that produces sequencing data after running for a day or two, the small sequencer generates enough data for pathogen detection and subtyping in about an hour-and-a-half, he said.

Deng tested the process on raw chicken breast, lettuce and black peppercorn samples treated with salmonella and retail chicken parts that were naturally contaminated with different serotypes of salmonella. In one case, a small amount of salmonella was detected and subtyped from lettuce samples within 24 hours. This takes two weeks using standard methods.

Identifying pathogenic bacteria before a food product is released into the market can reduce the number of people who get food poisoning, said Francisco Diez, director of the food safety center.

Deng’s work was featured in the February issue of Applied & Environmental Microbiology, a leading journal in the field.

Deng and his former graduate student, Shaokang Zhang, also created SeqSero, a cloud-based software tool that quickly classifies strains of salmonella. SeqSero is now used worldwide for salmonella surveillance.

Food safety center scientists from the University of Georgia College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences are also working to inactivate parasites that can contaminate fresh produce, kill bacterial pathogens on dry foods and identify factors that affect contamination of fresh produce before and after it is harvested.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)