Digital revolution stands to transform ag

Pace of change is increasing rapidly even within agriculture and is being spurred, in large part, by changes in digital age.

The pace of change is increasing rapidly even within agriculture, and in large part, it is being spurred by changes in the digital age, according to Aidan Connolly, chief innovation officer at Alltech.

Connolly believes that technological innovations have the ability to transform every link in the food chain, from seed to fork. He outlined his thoughts in a paper he shared recently via social media.

The topic also is a main focus of a symposium hosted by Alltech in Lexington, Ky., this week, which explores the need to embrace these innovations and the opportunities they hold, particularly given that there will be nearly 10 million people on the Earth by 2050.

Future improvements to crop and livestock productivity are critical. Connolly explained that overall, agricultural efficiency is still relatively poor. He said, for instance, that it takes seven tons of feed to produce just one ton of meat. Likewise, it takes 880 gal. of water to produce 1 gal. of milk.

Further, he said, climate change is requiring crop management changes, and access to fresh water and good soil are becoming serious limitations for agriculture.

The good news is that these and other issues can be reduced and/or eliminated through what Connolly referred to as the fifth agricultural revolution. He said there are eight emerging digital technologies that have the potential to transform agriculture. They range from specific technical tools to new ways of seeing the existing system.

“These eight digital technologies can be categorized into four each of hardware and software and when combined with the IoT (Internet of Things) can profoundly change the way food production works,” Connolly said.

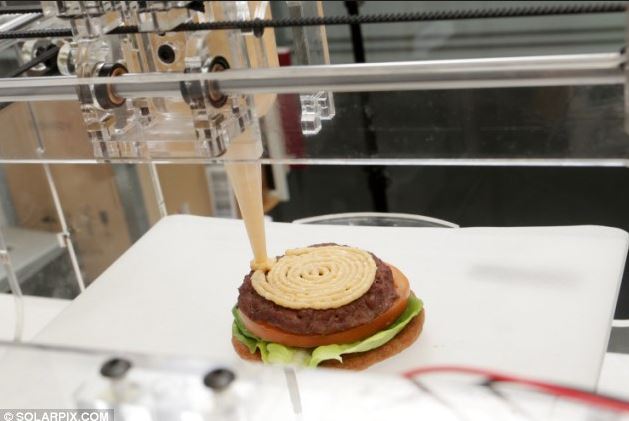

3D Printing: 3D printers are becoming familiar, but their potential is still massively untapped. This is particularly true in the agribusiness arena. There are obvious, easy applications on farm, as in using a 3D printer to create a needed part for a repair, thereby increasing self-sufficiency and avoiding potential losses in production. More ambitiously, it could allow farmers to develop alternative parts to suit their particular requirements. A veterinarian might use it to produce a weight-bearing support for a cow with a broken leg. As costs come down (older materials used to cost around $5-10 per cubic inch, but a material known as PLA has reduced costs to just $0.25-$0.50) the range of uses will expand. Some are already getting creative with other possible uses: Food Ink is a pop up dining experience in which not only is all of the food created through 3D printing, but so are the utensils and furniture. 3D food printers for home use are now being offered starting at $2,000, noted Connolly.

Robots: Robots are already accepted on many farms because they reduce labor costs, particularly for time consuming and repetitive tasks. However, now they are going to the next level: functioning autonomously or through set instructions to offer new kinds of assistance to people. For example, there are wine bots that are used in vineyards to prune vines, remove young shoots and monitor the vine and soil for general health. Nursery bots are used in plant nurseries to relocate potted plants. In the livestock industry, there’s a herder bot that will keep cattle moving in the right direction and another robot to mix the feed. There is a rotary robot that is changing up milking machines. Some dairy farmers even say the cows decide when it’s time to be milked. These new generation robots even include “soft robots” made from material and not from metal. Connolly said estimates are that the robot market in agriculture is expected to grow from just under $1 billion per year to $16 billion per year by 2020.

Drones: While a form of robot, they lend a specificity that should be acknowledged separately. Of primary interest to farmers is the ability to visit and observe parts of the field they cannot easily go during the growing season, and with new camera technologies to collect information not seen with the human eye. Drones are being used in soil and field analysis, planting, crop spraying/monitoring, irrigation and crop health assessment. Even companies that don’t specialize in this technology recognize the value: John Deere is incorporating scouting drones in a collaborative effort to extend its own offerings to customers. Syngenta and DuPont Pioneer both have made the foray into drone technology to assist farmers in making fertilizer application and irrigation decisions through aerial images. On the crop side, companies are using drones to analyze and monitor crop health focusing on improving yields and reducing costs.

Sensors: Sensors may soon be the most ubiquitous digital technology in agriculture, as they deliver a tremendous array of functions (covering a wide range of agriculture arenas, from crops to livestock) and very affordable. They can be used to analyze the air, water or soil of a field or a greenhouse, for example using the infrared spectrum that is otherwise invisible to the human eye. The resulting information can be analyzed and displayed graphically on a computer, allowing for detailed analysis and providing forecasts and remedies for problems such as drought or disease, said Connolly. He noted that sensors also include wearable technologies for livestock that can monitor movement, estrus cycles, healthy vitals and general herd identifying information. They can even be used to warn away predators by sensing the animal’s behavior through its movement and signaling flashing lights. The market for agricultural sensors is expected to reach $2.5 billion by 2025.

Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI takes the data gained from sensors and converts it to useful information. AI refers to machines that can mimic "cognitive" functions such as "learning" and "problem solving. An exciting example in agriculture is machine vision, where computers process visual data collected via UAV, satellite or even smart phones and provide the farmer with useful information. Most importantly companies are developing algorithms to identify animal behavior and productivity on an individual basis. AI is particularly important because it can interpret information far better than humans and can be used to filter data and allow humans to only become involved when it is absolutely necessary, Connolly said.

Augmented Reality (AR): AR, sometimes called mixed reality, is the addition of information, typically by computers or sensors, to that of the real world. It is the middle ground between reality and virtual reality. An example is the ability of computers to see spectrums of light that the human eye cannot pick up, but which might contain useful information for decision making. Food producers can use AR to layout the planting options in a field or by a fertilizer salesman to demonstrate the impact his product could have on his customer’s field. The argument with AR is that it is more than images superimposed on a computer screen, the user needs to actually see the virtual images as part of the real image before him (such as with Google’s Glass or Microsoft’s HoloLens or PokemonGo), Connolly said. The technology is still very expensive, but high-value uses such as identifying pathogenic bacteria in the food chain are likely to be among the early applications, he said.

Virtual Reality (VR): Adoption of VR technology will also be slowed by high implementation costs, but as with the other technologies here, the prices are coming down very quickly, Connolly said. A likely early use of VR is livestock video monitoring systems that send data back to a computer program, which in turn constructs a visual representation of the herd or brood allowing the farmer to check in on the cows or chickens remotely. VR is developing into an important training tool in many industries and is already an important teaching tool in veterinary medicine. A natural extension would be training employees and workers for on-farm work. Despite the many possible applications and uses, this is one technology that may still be a ways off from fully integrating itself into the agriculture industry, Connolly said.

Blockchain: As with the other technologies listed, a blockchain is a way of using technology to gather, interpret and share information. In this case, it is the information that goes along the food chain. Having a solid source of reliable information about food (including where it was grown; how it was processed, stored and transported; who was in control at each stage of the journey) has been a challenge ever since people started trading for food. These days, with an increasingly global food chain, and ever more complicated compliance requirements the information chain is even more important than ever. Blockchain is essentially an incorruptible electronic ledger that can track each transaction of a food item’s journey through the food chain. From a legal standpoint, the encryption allows for safekeeping of information, reducing the need for lawyers or legal action, said Connolly. Given that each year almost one in 10 people fall ill from consuming contaminated food; this technology has the potential to directly affect the consumer in a monumental way, he noted.

Together, these eight technologies are part of the Internet of Things (IoT), which is essentially the connectivity of machines in collecting, sharing and analyzing data. The connectivity has dramatic applications in the agribusiness sector, both crop and livestock, where there are significant geographical and information access challenges, said Connolly.

“These eight technologies discussed in this blog are already in play, representing tremendous opportunities for those who recognize the implications. Not just obviously agribusiness participants -- the farmers who recognize that they must be not just farmers of crops and animals but farmers of data -- but also food marketers who haven’t realized how connected with the larger business community agribusiness has now become,” said Connolly.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)