Agro-defense a 'real national security problem'

Senate Agriculture Committee hearing looked at vulnerabilities of U.S. farmers and economy from biological threats, as well as solutions to safeguard American agriculture from these threats.

Biological threats, whether naturally occurring like the avian influenza outbreak of 2015 or intentionally introduced, could pose great harm to the nation's food supply and economy. On Wednesday, the Senate Agriculture Committee held a hearing as an opportunity to take stock of how far the U.S. has come since the early 2000s, when the issue of agriculture security was first visited, and to discuss where to go from here.

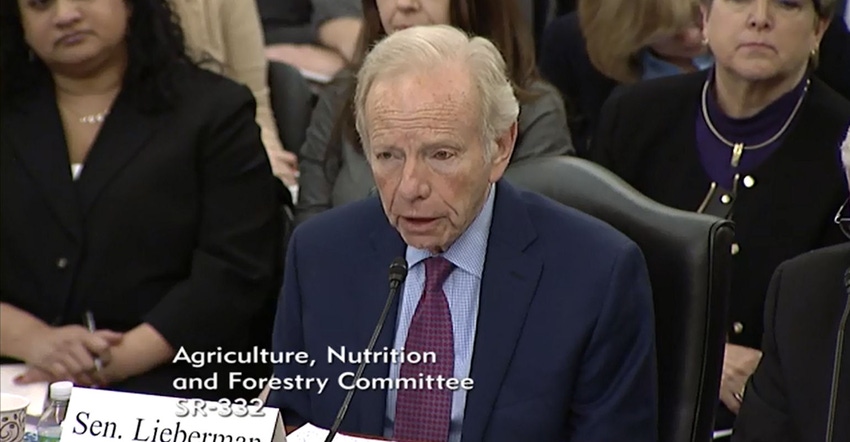

Former Sen. Joe Lieberman, who now serves at co-chair of the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, noted that, in evaluating the challenges in agro-defense and developing recommendations over the last year, it became evident that agro-defense is a “real national security problem.”

“If you’re an enemy and you wanted to strike us, nuclear weapons get the most attention,” Lieberman said. However, if you want to create a real sense of terror and deal damage to the economy, attacking the U.S. agricultural system with a pathogen would be devastating.

Senate Agriculture Committee chairman Pat Roberts (R., Kan.) said he assured those who testified that every member of the committee is aware of the threats posed to the U.S.

In summary at the end of the meeting, he said although progress has been made in areas, the nation still has a lack of vaccines, lack of coordination, lack of response capability, lack of funding, lack of awareness and lack of intelligence capability.

Dr. Doug Meckes, state veterinarian and director of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services’ Veterinary Division, provided details on revisiting the Homeland Security Presidential Directive 9 (HSPD-9). Released in January 2004, HSPD-9 “established a national policy to defend the agriculture system against terrorist attacks, major disasters and other emergencies.”

Meckes reported that 13 years later, progress has been made on addressing some of those gaps, not the least of which is the “star in the crown” with the creation of a national bio-defense center that will be established in Kansas.

At the top of the list of gaps in the current bio-defense system is the absence of needed vaccines as part of a national veterinary stockpile containing sufficient amounts of animal vaccine, antiviral or therapeutic products to appropriately respond to the most damaging animal diseases affecting human health and the economy and that will be capable of deployment within 24 hours.

“We have not yet achieved this goal. Our animal agriculture industry remains as vulnerable to foreign animal diseases today as it was 13 years ago; particularly concerning is foot and mouth disease (FMD),” Meckes said.

He noted that many agricultural groups, animal science organizations and veterinarians support the inclusion of a new Animal Disease & Disaster Prevention Program in the 2018 farm bill. Additionally, a proposal for establishing and funding a robust U.S. FMD vaccine bank in the 2018 farm bill is considered a top priority by many in the animal agriculture industry.

Lieberman explained that animal agriculture is central to the health and well-being of the American people and the U.S. economy. His panel wanted to better understand the continued risks at the nexus between animal agriculture and national security, but one of the most unsettling effects of the report was that nobody in the government could pinpoint how much money was being spent on agro-defense. “If nobody can tell how much is being spent, you can’t figure out if you’re spending it wisely,” he said.

Lieberman also voiced support for creating a prevention animal health fund, much like the one the 2008 farm bill established for plant health.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like